A lot has changed in the world since I last posted.

I have been extremely lucky during this pandemic. I am still employed, I can work from home, and I have my wife to shelter with. I do not take these things for granted.

And yet.

While my work life has not changed as drastically, my personal life has. Most of the things I did outside work before the pandemic were in person. Can’t do that right now. So, it gave me some time to work on home-bound projects that I pushed back on the shelf.

To that end, I’m very excited to introduce PCG, or Point and Click Game engine, an adventure game creation utility for the open web.

I did a talk about it three years ago (ouch), so this project has certainly been a long time coming.

PCG is very much in active development, but I think I’ve made encouraging progress, which I’ll explore in detail later.

But first, what am I talking about?

What is an adventure game?

If this is old hat to you, skip ahead to the next section.

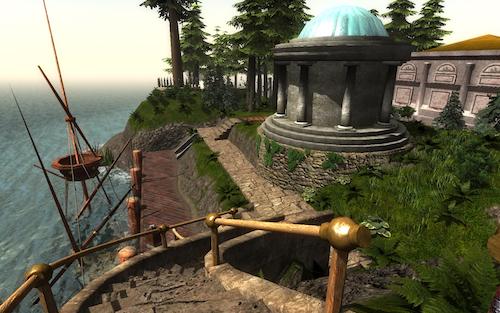

For those not familiar, a point and click adventure game is a style of narrative, story-based games where progress is made primarily through puzzle solving, rather than violence or reflexes, something I appreciate more and more as I age.

While their popularity peaked in the early 90s for mainstream gaming cultural, they have thrived in the indie space over the past decade or so.

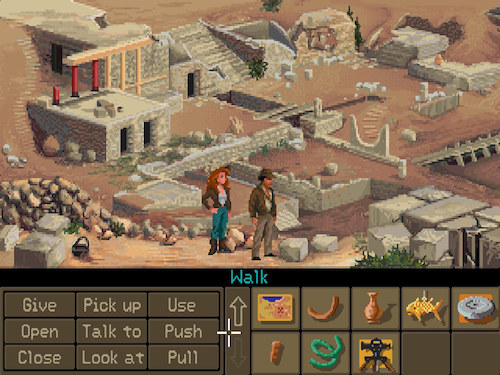

Mechanically, many games in the genre use a system of verbs to interact with the world. You click a verb from a menu, for example “push”, and then the person or object in the game you want to apply it to, such as “crate”. Perhaps there would be a trap door below the crate, and a new area is unlocked.

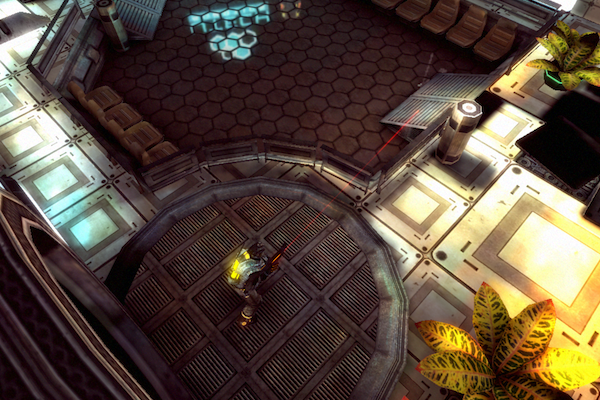

Another method some games employ is to do away with the specific list of verbs, having pre-determined actions when interacting, or relying on the levers that must be switched in the right order.

Almost all have you collecting various esoteric items, having the player apply those items to people or objects in the game, or combining them with each other.

A relatively simple system, from a game mechanics perspective, but one that hides a lot of depth, story-telling potential, and that particular player satisfaction from figuring out a puzzle.

Why a web-based adventure engine?

Most innovation in the web game space is around the <canvas>

element and Web Assembly, which allows developers to “start from

scratch” and create entirely custom rendering divorced from any of

the preconceptions of the web.

This works well for action games or games with pixel-pushing graphics. However, the goal here is always to emulate a native application, and since games written for the browser cannot by definition ever be native, the best they can be is a close approximation.

While close might be good enough, this always felt like a missed opportunity to me. We spend all these resources trying to get the web to be more like native applications, but hardly any on what new and interesting experiences we can create that are unique to the web. As Marshal McLuhan wrote, an author I’m proud to say I got a few pages into, the medium is the message.

I started thinking about what kind of games would work well inside the traditional web context - aka, HTML, CSS and JavaScript (and SVG) rendered into a DOM tree.

After some thought, I settled on point-and-click adventure games.

My reasons being:

- They are not real-time games—Having game play that relies on any kind of precise timing are going to need a more controllable rendering model than the traditional web.

- They rely on text/audio—Text is a first class citizen of the web, and new web audio APIs make that aspect possible.

- They are narrative-driven—The web is a powerful method of communication, and I’m excited by new methods of leveraging that.

- I like them :smile:—This is important, because without it I wouldn’t be able to finish a big project like this.

In short, I thought I could re-create many of the different point and click adventure paradigms on the web, while taking full advantage of the things that make the web the web.

Some of the unique things that are attractive about the web are:

- It’s universal—Many more people have access to a web browser than those with access to a machine that can play a triple A game.

- It’s accessible by default (with a rich API for extensions)—This enables access by those with visual, auditory, motor, or other disabilities. Accessibility is sadly an afterthought in a lot of digital design, and seems entirely absent in the gaming space. Treating accessibility as a first class citizen makes the experience better for everyone.

- It’s sharable—An oft taken for granted killer feature of the web is URLs. The power of sharing a permanent link that will work in every browser and can be posted to any platform is one I cannot understate.

Design goals

The ultimate goal of PCG is to foster a open, welcoming, and creative community around making point and click adventure games on the web.

In game engine terms, the goal is to create a flexible, modular, and pluggable system of components that can be combined to create most if not all the point and click varieties mentioned above (and many that were not), as well as opening up the possibility for new and unique games only possible in the web format.

After a lot more thought, writing, re-writing, trial and error, and leveraging embarrassingly earned career experience, I settled on some design principles for PCG.

The thought of even having design principles was something hard earned, but one I strongly believe in: a north star for how you go about making something out of nothing.

- Leverage core web tech (HTML/CSS/JS)—Rely on core web technologies and patterns over writing new systems. While new systems may offer benefits, building off existing ones usually means a more familiar, fast, and pleasant player experience.

- Player experience over developer experience—While developers are important, the end result that players consume takes precedence over the experience of the developers creating the game. These first two principles are why PCG is built without a framework in vanilla HTML/CSS/JS.

- Through documentation—A well documented system is an understood system, and an understood system is a powerful tool.

- Newbie friendly—As the web has professionalized, many exciting capabilities have opened up. It has also raised the barrier to entry. Creating something fun and expressive that can be used at a basic level to good results, while still offering a much larger world of possibility for those interested in learning, I think strikes the right balance.

- Open source—This is essential to creating a community, which is critical to the success of a tiny project like this. I also believe in it.

Next steps

This is a very high level introduction to the ideas surrounding the PCG project. I plan on writing posts going in-depth on each component of the system as they’re built and as updates are made. These posts will hopefully serve as a living progress report.

While I’ve spent a lot of time on PCG already, it is still in the beginning stages. It is very much a leap of faith.

I can’t predict what kind of community it will attract, if any, or what this project may or may not evolve into.

But I am excited to find out.

You can check out the Github repository or the documentation site for PCG, both very much in progress. If you have any feedback or would like to contribute, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

If you’d like to see what PCG is capable of currently (as much as I cringe to reveal the multitude of missing features) my friend made a tiny, rough demo game, and I made a little demo showcasing the text box component.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end, hope you and yours are safe and healthy, and I’ll catch you on the next adventure.